One of our readers recently left a comment on a post about vocalist Dick Robertson that we published a couple of years ago, requesting a similar article about Elmer Feldkamp, a singing reedman who recorded quite often with some name bands in the 1920s and '30s but about whom not much is known. In fact, not even a single promotional picture of Feldkamp seems to have survived. I accepted the challenge and set about piecing together as much information as I could find about Feldkamp, with some invaluable help from a handful of fellow vintage jazz enthusiasts from the British Dance Bands Yahoo Group, to whom I am extremely grateful. Here is, then, a brief sketch about the largely unknown life of Elmer Feldkamp.

From the 1920s on it became common practice to feature brief vocal refrains on many dance band records, which proved so successful with the public that by the 1930s there were several singers, such as Dick Robertson and Chick Bullock, to name but two, who restricted their work to the recording studio and did not see the need to tour or appear live on stage. This was, however, not the case with Elmer Feldkamp, who besides providing vocals for recordings by the bands of Bert Lown, Roger Wolfe Kahn, and Freddy Martin, was also highly regarded as a saxophone and clarinet player with those orchestras and even got to front his own outfit for a time and star on radio. Despite his popularity in the late 1920s and all through the '30s, his career was tragically cut short by his death in 1938, and today he remains an extremely obscure figure whose recordings have not been reissued on CD, except for a few of the sides he cut as a sideman and band vocalist. As a matter of fact, before setting out to write this post, all I knew about Feldkamp was that he was the featured singer on some of the tracks included in a Bert Lown CD compilation released by the Old Masters label a few years back.

Born into a musical family in New Jersey on April 8, 1902, to German parents, Elmer Feldkamp quickly showed an interest in music. as did his brother Walter, a successful pianist with whom Elmer would team up at various times throughout his rather brief career, at one point in 1932 even duetting with him on piano on radio. Another one of his brothers, Fred, became popular as a journalist and author and was founding editor of For Men Only, a famous men's magazine first published in the late 1930s. Elmer learned to play clarinet and saxophone at college, and by 1927 he had formed his own band, Elmer Feldkamp and His Churchill Downs Orchestra, which took the name from the hotel in Kentucky where the band was headquartered and from where it broadcast regularly. The gig did not last long, though, because by the end of the decade, Feldkamp had joined the popular orchestra led by Bert Lown at New York's Biltmore Hotel, playing the clarinet and providing vocal refrains for several of the band's Columbia and Victor recordings. Besides cutting records with Lown, in 1930 Feldkamp was also featured on his own radio show, Morning Melody, which aired on station WEAF, in New York. Throughout 1930 and 1931, he recorded with several studio-only orchestras on ARC/Brunswick and also joined Fred Rich, with whom he made a few sides, as well as some regular broadcasting.

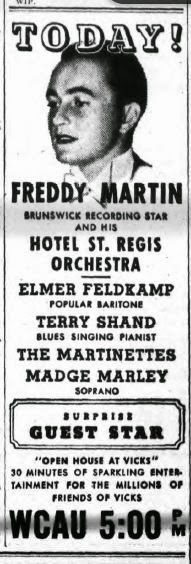

Then in early 1932 Feldkamp made a major career move by joining the Freddy Martin orchestra, where he would remain for the rest of his career playing the alto sax and the clarinet, as well as contributing vocals. He did not seem to have an exclusive contract with Martin, though, since during this time he also recorded with his brother Walter and with Roger Wolfe Kahn, and he also cut some discs for Crown Records in 1932 and 1933 under his own name as the leader of a studio group that was made out of a few of Martin' sidemen. An ad for a Vicks-sponsored radio series starring Freddy Martin called Vicks' Open House, inserted in the Philadelphia Enquirer in October 1934, attests to Feldkamp's popularity within the ranks of the Martin orchestra, as his name appears right under the bandleader's, and he is billed as a "popular baritone." Also in 1934, Feldkamp appeared on the air as the regular vocalist with Merle Johnston, and after that, besides his work with Freddy Martin, we begin to lose track of his activities. That is, of course, until his untimely death from heart failure on September 27, 1938. A quick look at Feldkamp's death certificate shows that he suffered from several illnesses, including appendicitis, peritonitis, and a heart condition, any of which could have caused his sudden death. Yet, surprisingly, an obituary note published in the New York Evenibg Star on October 5, 1938, seems to suggest that there may have been a darker side to Feldkamp's personality. The news report reads as follows:

Whether Feldkamp's inferiority complex regarding his brothers Walter and Fred was a figment of the anonymous writer of this piece or not, the truth is that Feldkamp did not really have a reason to feel overshadowed by his siblings. A fine musician and vocalist, he recorded with some of the top bands of the '20s and '30s, and his music, though sadly neglected by CD reissue companies, deserves to be rediscovered. Some sides featuring Feldkamp, under his own name and as a provider of vocal refrains, are available at the Internet Archive, and the CD Bert Lown's Biltmore Hotel Orchestra Featuring Adrian Rollini & Tommy Felline (The Old Masters MB 105) offers a good sample of tracks that include Feldkamp, recorded for Columbia and Victor between 1930 and 1931. Feldkamp sounds self-assured and shows a good sense of timing on all his solo sides with Lown, as is the case on "I'll Be Blue, Just Thinking of You," "The Penalty of Love," "Lonesome Lover," "They Satisfy," and especially on "Please Don't Talk About Me When I'm Gone," "You Call It Madness," "Sweet Summer Breeze," "I Can't Get Mississippi Off My Mind," and "Blues in My Heart." Realizing that Feldkamp's melodious baritone was perfect for harmonizing in a vocal trio, Lown used him often in such as setting with wonderful results, first as part of the Biltmore Rhythm Boys, with Paul Mason and Tommy Felline ("Under the Moon It's You," "Bye Bye Blues," "Here Comes the Sun," "Loving You the Way I Do") and later as the Biltmore Trio, with Mason and Mac Ceppos ("You're Simply Delish," "Crying Myself to Sleep," "To Whom It May Concern," "Heartaches," "When I Take My Sugar to Tea"). By 1933, Feldkamp had moved on to the Freddy Martin orchestra and had been replaced by Ted Holt, yet he made some of his best recordings during his tenure with Lown, blending perfectly into a band that included such fine musicians as Adrian Rollini, Tommy Felline, and Chauncy Gray, and playing arrangements that occasionally left space for some hot solos.

I would like to thank British Dance Bands Yahoo Group members Mr. John Welch and Mr. Terry Brown for all their help with the research for this piece on Elmer Feldkamp. In particular, without the assistance of Mr. Brown, who provided me with biographical data and photographic and journalistic material, this article could never have been written, so I remain eternally grateful.

From the 1920s on it became common practice to feature brief vocal refrains on many dance band records, which proved so successful with the public that by the 1930s there were several singers, such as Dick Robertson and Chick Bullock, to name but two, who restricted their work to the recording studio and did not see the need to tour or appear live on stage. This was, however, not the case with Elmer Feldkamp, who besides providing vocals for recordings by the bands of Bert Lown, Roger Wolfe Kahn, and Freddy Martin, was also highly regarded as a saxophone and clarinet player with those orchestras and even got to front his own outfit for a time and star on radio. Despite his popularity in the late 1920s and all through the '30s, his career was tragically cut short by his death in 1938, and today he remains an extremely obscure figure whose recordings have not been reissued on CD, except for a few of the sides he cut as a sideman and band vocalist. As a matter of fact, before setting out to write this post, all I knew about Feldkamp was that he was the featured singer on some of the tracks included in a Bert Lown CD compilation released by the Old Masters label a few years back.

|

| Bandleader Bert Lown |

|

| The Freddy Martin Orchestra in the 1930s. Elmer Feldkamp is said to be on the front row, far right |

Then in early 1932 Feldkamp made a major career move by joining the Freddy Martin orchestra, where he would remain for the rest of his career playing the alto sax and the clarinet, as well as contributing vocals. He did not seem to have an exclusive contract with Martin, though, since during this time he also recorded with his brother Walter and with Roger Wolfe Kahn, and he also cut some discs for Crown Records in 1932 and 1933 under his own name as the leader of a studio group that was made out of a few of Martin' sidemen. An ad for a Vicks-sponsored radio series starring Freddy Martin called Vicks' Open House, inserted in the Philadelphia Enquirer in October 1934, attests to Feldkamp's popularity within the ranks of the Martin orchestra, as his name appears right under the bandleader's, and he is billed as a "popular baritone." Also in 1934, Feldkamp appeared on the air as the regular vocalist with Merle Johnston, and after that, besides his work with Freddy Martin, we begin to lose track of his activities. That is, of course, until his untimely death from heart failure on September 27, 1938. A quick look at Feldkamp's death certificate shows that he suffered from several illnesses, including appendicitis, peritonitis, and a heart condition, any of which could have caused his sudden death. Yet, surprisingly, an obituary note published in the New York Evenibg Star on October 5, 1938, seems to suggest that there may have been a darker side to Feldkamp's personality. The news report reads as follows:

Elmer Feldkamp was the vocalist for Freddie Martin's orchestra. His brother, Walter Feldkamp, conducts his own orchestra and furnished the music at the Stork Club last year. Another brother, Fred Feldkamp, edits the magazine for men [For Men Only]. And so Elmer felt himself overshadowed by his brother's [sic] accomplishments, but vowed that some day he'd be a national figure. The current issue of Collier's, the national magazine, has a swing-music story called "Cats Love Music." One of the leading characters in the story is Elmer Feldkamp. But the youngster never read the story. He died in San Francisco last Tuesday.

Whether Feldkamp's inferiority complex regarding his brothers Walter and Fred was a figment of the anonymous writer of this piece or not, the truth is that Feldkamp did not really have a reason to feel overshadowed by his siblings. A fine musician and vocalist, he recorded with some of the top bands of the '20s and '30s, and his music, though sadly neglected by CD reissue companies, deserves to be rediscovered. Some sides featuring Feldkamp, under his own name and as a provider of vocal refrains, are available at the Internet Archive, and the CD Bert Lown's Biltmore Hotel Orchestra Featuring Adrian Rollini & Tommy Felline (The Old Masters MB 105) offers a good sample of tracks that include Feldkamp, recorded for Columbia and Victor between 1930 and 1931. Feldkamp sounds self-assured and shows a good sense of timing on all his solo sides with Lown, as is the case on "I'll Be Blue, Just Thinking of You," "The Penalty of Love," "Lonesome Lover," "They Satisfy," and especially on "Please Don't Talk About Me When I'm Gone," "You Call It Madness," "Sweet Summer Breeze," "I Can't Get Mississippi Off My Mind," and "Blues in My Heart." Realizing that Feldkamp's melodious baritone was perfect for harmonizing in a vocal trio, Lown used him often in such as setting with wonderful results, first as part of the Biltmore Rhythm Boys, with Paul Mason and Tommy Felline ("Under the Moon It's You," "Bye Bye Blues," "Here Comes the Sun," "Loving You the Way I Do") and later as the Biltmore Trio, with Mason and Mac Ceppos ("You're Simply Delish," "Crying Myself to Sleep," "To Whom It May Concern," "Heartaches," "When I Take My Sugar to Tea"). By 1933, Feldkamp had moved on to the Freddy Martin orchestra and had been replaced by Ted Holt, yet he made some of his best recordings during his tenure with Lown, blending perfectly into a band that included such fine musicians as Adrian Rollini, Tommy Felline, and Chauncy Gray, and playing arrangements that occasionally left space for some hot solos.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank British Dance Bands Yahoo Group members Mr. John Welch and Mr. Terry Brown for all their help with the research for this piece on Elmer Feldkamp. In particular, without the assistance of Mr. Brown, who provided me with biographical data and photographic and journalistic material, this article could never have been written, so I remain eternally grateful.

|

| Though currently out of print, this ASV/Living Era Freddy Martin CD features some sides with Feldkamp on vocals |