Known for her perfect pitch and for being one of the favorite singers of servicemen during World War II, Jo Stafford is also one of the most interesting postwar pop vocalists, undoubtedly because of a singing style that mixed sweetness and sentiment with jazzy nuances. This is already apparent in her early 1940s recordings with Tommy Dorsey, both as a featured "girl singer" and as a member of the hugely popular vocal group The Pied Pipers. And for anyone who still may doubt her stature as a jazz vocalist, there is also Jo + Jazz, her outstanding jazz-inflected LP cut in 1960. But the objective of today's post is not to make a case for Stafford as a jazz singer, but rather to take a look at the exceptional Yuletide recordings that she made in the 1950s and '60s, which are readily available on two CDs that any serious classic pop aficionado should own.

The first of them is Happy Holidays (Corinthian Records, 1999), a collection of twenty-two songs that are loosely linked by their wintry theme. While some of them ("June in January," "Hanover Winter Song," "Let It Snow") explicitly mention the winter season, others simply evoke a setting that suggests the need to stay cozily indoors enjoying the warmth of a crackling fireplace (like Jo herself on the cover of this release), as is the case with "By the Fireside," "The Nearness of You," "I've Got My Love to Keep Me Warm," and "Moonlight in Vermont." This is possibly the main reason for the subtitle of the CD, I Love the Winter Weather, which is also a reference to Stafford's outstanding version of the tune "Winter Weather," which is also included. And then, of course, there are also plenty of Christmas songs, both traditional and more modern, such as "Sleigh Ride," "The Christmas Song," "Oh Little Town of Bethlehem," and "Silent Night," to name but four. One of the gems in the collection is the old traditional hymn "I Wonder as I Wander," which Stafford sings in a highly melancholy way that befits the song perfectly. Most of the tracks were recorded in the mid 1950s, and the arrangements by Paul Weston, Stafford's husband and lifelong musical partner, are as classy and thoughtful as usual. Weston's studio orchestra includes fine musicians such as Ted Nash, Babe Russin, and Ziggy Elman, and both The Starlighters and the Norman Luboff Choir lend choral support to the proceedings.

Almost a decade later, in 1964, when Stafford was slowly retiring from the music business, she entered the Capitol studios to cut The Joyful Season (DRG Records, 2005), a delightful classic that would become one of the last albums of her career. This time the idea was that Stafford would overdub her own voice several times, in the manner of the Les Paul and Mary Ford hit records of the 1950s, in order to create the illusion that she was singing as part of a vocal group. And, as Will Friedwald observes in the liner notes to the CD reissue, the idea was successful:

The overall result is a unique sound that combines the passion and the power of the sacred with the excitement and the energy of the secular—and a mighty welcome stocking-stuffer indeed.

Weston is again handling the arrangements, which are rather subdued so that Stafford's multi-tracked voice shines brightly on absolutely every song, and the tunes cover a wide range of Christmas music, from sacred hymns to modern Christmas pop songs to two songs newly written by Weston with Alan and Marilyn Bergman—the lovely "Merry Christmas" and "Christmas Is the Season." The CD release includes two tracks not on the original album ("Gesu Bambino" and "Ave Maria"), as well as two marvelous Christmas medleys on which Stafford teams up with Gordon MacRae. The disc closes with "Toys for Tots," which Stafford recorded for the Marine Corps, and the whole collection stands as G.I. Jo's most enduring contribution to the Christmas pop canon.

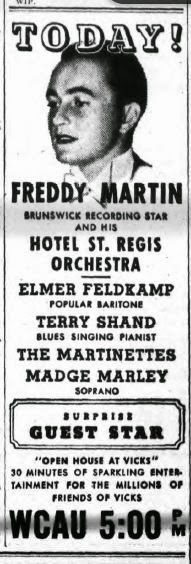

|

| Jo Stafford and her husband, arranger Paul Weston, in the early 1950s |